‘It stirred the people to breathless wonder and scalding abuse’: The tumultuous history of the Sydney Opera House Myles Burke

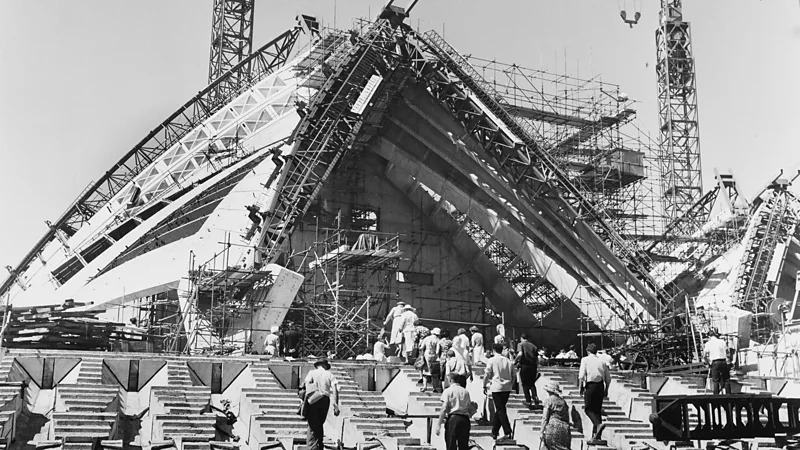

‘It stirred the people to breathless wonder and scalding abuse’: The tumultuous history of the Sydney Opera House The construction of the Sydney Opera House commenced on March 2, 1959. However, when BBC Tonight visited the building site in 1965, it was beset by technical issues, rising prices, fluctuating public opinion, and political infighting.

In 1965, BBC correspondent Trevor Philpott stood overlooking Sydney Harbour and sought to find the proper metaphor to depict the bright, arching structures of Jørn Utzon’s roof design for the Australian Opera House. “There were scores of towering shells. It was a group of seagulls extending their concrete wings. “It was a huddle of sailing boats with billowing concrete sails,” Philpott explained. He immediately added the caution, “And it was an absolute nightmare to build.”

The problematic building of the Sydney Opera House began on March 2, 1959, which is 66 years ago this week. Six years later, when BBC Tonight’s Philpott visited the site, it was already years behind schedule, with spiraling expenses, shifting designs, and growing political tensions. To say it was a tough birth is an understatement.

Sir Eugene Goossens

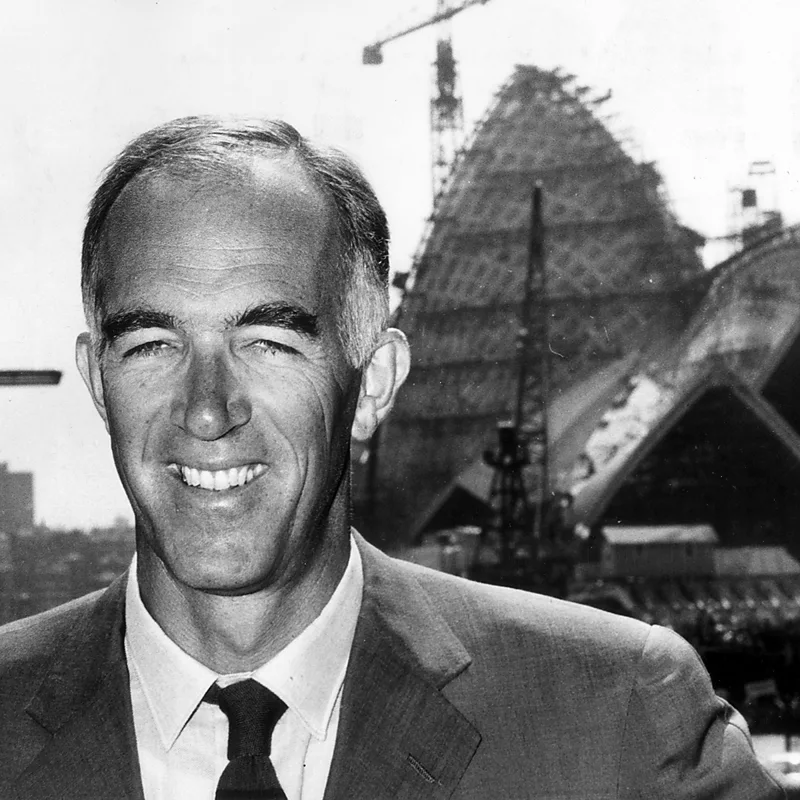

Sir Eugene Goossens, an accomplished English conductor, advocated the idea of building the city’s opera house in the late 1940s. At the time, Goossens was a classical music star, having established a lucrative career in the United Kingdom and the United States. Following World War II, he was attracted to Sydney to become the director of the New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music with the prospect of a salary larger than that of the Australian Prime Minister, according to musicologist Dr Drew Crawford on the BBC program A Very Australian Scandal in 2023.

The conductor’s lifelong dream was to build a new, world-class music performance arena. He had seen from his office window what he thought was the perfect location for it: the tram depot at Bennelong Point. Tubowgule, known to the local indigenous Gadigal people of the Eora tribe, was a site of Aboriginal festivals for thousands of years. Throughout the 1950s, Goossens campaigned tirelessly to make his goal a reality. “There were very few other people who could have that vision, articulate that vision, and have the ear of the Premier [of New South Wales], have the ear of the Prime Minister, be able to talk to people to get it going,” pointed out Dr. Crawford.

Trevor Philpott dubbed it the Sydney Harbour monster, a slice of Danish pastry, and a crumbling circus tent.

Goossens persuaded

Goossens persuaded New South Wales Premier Joseph Cahill that an opera house would reshape the world’s perception of Australia, that he had found the ideal location for it, and that they should hold “a grand competition, open to architects from all over the world, to decide exactly what kind of a building they should put there,” said Philpott. “They made only one condition, that nothing quite so remarkable should have been ever built before.”

Goossens would not see his dream realized. In 1956, after receiving his knighthood in the United Kingdom, he was held upon his return to Australia, when his suitcases were inspected and found to contain, among other things, smuggled pornography, compromising pictures, and rubber masks. The subsequent controversy, which included relationships, erotica, and witchcraft, effectively ended the conductor’s career in Sydney. He departed the nation for Rome, under the identity Mr E Gray, and never returned.

However, the design competition proceeded as scheduled, with a panel of judges reviewing about 233 submitted concepts. At the start of 1957, the government declared that Utzon, a completely unknown Danish architect, was the unexpected winner. Part of the astonishment at Utzon’s achievement stemmed from the fact that his application was mostly made up of preparatory sketches and concept drawings. “As far as building anything of any scale, he hadn’t really done very much,” Sir Jack Zunz, who worked on the project for the civil engineering firm Arup, told BBC Witness History in 2018.

An hopeful start.

The judges’ decision of Utzon’s daring and inventive design was not without debate. “From the first, it stirred the people of Sydney to breathless wonder and scalding abuse,” Philpott recalled. “It was called the Sydney Harbour monster, a piece of Danish pastry, a disintegrating circus tent.”

Premier Cahill pushed for construction to begin as soon as possible, concerned that negative public opinion or political opposition might delay the project. This was despite the fact that Utzon was still working on the building’s real design and had yet to address crucial structural difficulties. Although Utzon’s design was deemed to be one of the most cost-effective, getting funds for it remained difficult, so a State Lottery was established in 1957 to assist with the project.

The initial estimate for the total cost of the Sydney Opera House was A£3.5 million, or A$7 million; at the time, Australia’s national currency was the pound, which was replaced by the dollar in 1966. The building was scheduled to open on January 26, 1963, Australia Day. Both of these projections turned out to be enormously and stupidly optimistic. “Right from the beginning, the house was full of trouble: human, mechanical, structural,” says Philpott.

The construction of the Opera House was separated into three phases: platform, roof shells, and interior. Cahill convinced the Minister of Transport to destroy the tram depot to build the podium, but “found the site was neither big enough nor strong enough to carry that structure that seemed on paper light enough to fly away,” according to Philpott.

If you got into a cab, you got an earful of all the money that was being spent. Sir Jack Zunz

To support the weight

To support the weight of the Opera House, the entire site had to be enlarged and strengthened by drilling over 550 steel-cased concrete shafts, each three feet in diameter, into ground in and around Sydney Harbour. This considerable work, which had not been factored into the building budget or timeline, went on, exacerbated by poor weather. The podium would not be built until January 1963, which was the initial date for the Opera House to open.

However, this would be only the beginning of the project’s delays and exorbitant additional expenses. The Opera House’s most distinguishing feature, its roof shells that resembled a ship’s sails, proved to be a source of additional engineering challenges. Initially, the goal was to build the roof out of steel covered with concrete. However, such design created unpleasant noise difficulties for any performance going place. “The Opera House stars would have been singing above the sirens of the tugboats on the water outside, and the temperature variations would have caused the metal and concrete to rumble and crack like tropical thunder,” according to Philpott.

An unbuildable building

Nobody had really grasped the magnitude of the engineering task that the Opera House’s ambitious curving roof surfaces represented. Because Utzon’s entry lacked specific technical designs, civil engineering company Arup was brought in to figure out how to build the roof’s complicated shell structure. However, after many redesigns, they were unable to make the structural calculations equal up. “The first thing Arup did when invited to assist was take these unconstrained forms and build a set of mathematical models that, as closely as possible, resembled Utzon’s competition design. None of these forms seemed buildable,” Zunz told BBC Witness History.

Another concern was that each concrete rib supporting the roof was unique due to its curvature. That meant that rather than having a single mould that could be reused to cast all of the supporting beams, each rib would require its own. It was too pricey.

Utzon subsequently said that the solution came to him when he was peeling oranges. The architect recognized that all of the roof segments could be derived from a single sphere’s geometry. By determining which section of the sphere best fit the forms they need, a sequence of triangles with one curved side could be sliced from it, resulting in a variety of shells. These spherical shell segments may be disassembled into separate components that could be evenly precast in concrete and installed on-site. “He returned a week later and said, ‘I’ve fixed it.'” And he created the idea out of a sphere,” explained Arup’s Zunz. “But in so doing, he had changed the architecture quite radically.”

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC’s unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

This clever technique

This clever technique streamlined roof construction and decreased waste, allowing work on the vaulted roof to begin in 1963. However, as the contractors tried to realize Utzon’s vision, the project was plagued by labor disputes, design modifications, and growing material costs, causing the budget to inflate and the anticipated completion date to fade into the distance. “By 1962, the cost had risen to A£12.5m, and now everybody admitted they were only guessing,” according to Philpott. “The opening day was repeatedly postponed. It was supposed to open on Australia Day in 1963, but it was postponed until early 1964, then again until sometime in 1966, and no one is daring to estimate the year it will finally open.”

Premier Cahill, the project’s most prominent government booster, became sick only months after construction began. On his deathbed in 1959, he had his Minister of Public Works, Norman Ryan, swear not to let the Opera House fail. When questioned by the BBC’s Philpott in 1965, Ryan gave a strong defense of the project, but his displeasure with the project’s growing expenses and unending delays was obvious. “I wasn’t sure whether to admit to working on it at the time,” Zunz told me. “If you went into a taxi, you got an earful of all the money that was being wasted, and God knows what.”

A few months after Ryan’s

A few months after Ryan’s BBC interview, Robert Askin, who had actively opposed the project, was elected Premier of New South Wales, exacerbating the tension. He nominated Davis Hughes as the new Minister of Public Works, who frequently battled with Utzon. Hughes, keen to save expenses, began to question the architect’s budgets and timelines, requesting a complete set of working drawings for the interiors – the project’s next step. “The whole situation started going downhill,” Zunz told me. “Utzon couldn’t, wouldn’t, and did not produce the

papers that his client requested.” In retribution, Hughes denied the construction team’s demands, leaving Utzon unable to pay his employees. In 1966, the Danish architect withdrew from the project and departed Australia, never to see the Opera House completed.

Utzon’s resignation sparked a public uproar, with 1,000 protesters going to Sydney streets on March 3, 1966, to seek his reinstatement. Instead, Hughes recruited a fresh panel of Australian architects to finish the interior and glass walls. But if Hughes thought this would save expenses and speed up the project, he was profoundly wrong.

Overcoming the odds

The new team destroyed the majority of Utzon’s interior blueprints and completely rebuilt it. Utzon had envisioned the main hall serving as both an opera and concert venue, but this was now deemed unfeasible, necessitating the demolition of the stage production gear that had already been installed. The new design also required that each of the hundreds of pieces of glass in the inside walls be cut to a unique size and shape, which added to the expenditures. The Sydney Opera House’s spiraling costs were exacerbated in 1972 by a labor dispute involving the layoff of a worker and requests for greater salaries, which ended in a sit-in strike on the site.

But the following year, the colossal task of building the Sydney Opera House was finally finished. It cost A$102 million (£51 million), ten years late and 14 times more than its original budget.

Queen Elizabeth II formally opened it on October 20, 1973. The king hailed the spectacular structure that had “captured the imagination of the world,” while also sarcastically adding that “I understand that its construction has not been completely trouble-free.” Utzon declined to attend the opening, writing to Premier Askin that he couldn’t “see anything positive” in the interior work done by the Australian architects and that it would be impossible for him “to avoid making very negative statements”.

More like this:

• The first ever video game console

• How the fall of the Berlin Wall reshaped Europe

• How music saved a cellist’s life in Auschwitz

In 1999, the Danish architect reconciled with the Sydney Opera House project and agreed to work on the A$66 million (£33 million) interior makeover. The Reception Hall was renamed the Utzon Room in his honor in September 2004, following his remodeling.

Since its construction, the Sydney Opera House’s imaginative architecture has received widespread recognition. Its unusual sculptural form has made it one of the most instantly identifiable structures in the world. More than 10.9 million people visit it each year, and its soaring roof represents Australia’s national character, celebrating innovation, culture, and ambition in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Bob Dylan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sammy Davis Jr. have all performed at the arena, as have The Cure, Björk, and Massive Attack. Arnold Schwarzenegger won his final bodybuilding title there in 1980, and ten years later, anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela delivered one of his first significant addresses from its steps after being released from jail. In 2004, Cathy Freeman, the first Aboriginal athlete to win an individual Olympic gold medal, began the Olympic torch relay from outside the building. Its eye-catching roof is lighted every year as part of Vivid Sydney, the city’s celebration of light, music, and ideas, and in 2017, bright animations depicting Indigenous Australian stories were projected onto it.

officially recognized

Unesco officially recognized the structure as a World Heritage Site in 2007. When proposing its inclusion, the International Council on Monuments and Sites stated: “The Sydney Opera House stands by itself as one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity, not only in the twentieth century, but throughout human history.”